The gear question I tend to get most often is, “what kind of hiking shoes should I get?”. “I don’t know. I’ve never used your feet,” is typical as my reply. The feet are the most vital set of hiking equipment we have determining, perhaps quicker than anything else, whether a hike is ultimately remembered fondly. It is also a defining factor for novices as to whether they stay with hiking. Cheryl Strayed went into excruciating detail about her feet in her book Wild, ultimately leading to losing her boots over the side of a cliff. As far as I remember, her feet were not in them at the time.

My feet are highly personal to me. I am the only one that ever uses them. I never loan them out. And like most earth traversing bipeds, we have plenty of time to think while hiking. So I developed my Philosophy of Feet. There are plenty of great websites that give all the basic advice on shoe selection. This post is about coming to terms with our feet and and perhaps confronting a myth or two that leads to expensive purchases, and of course, extra weight.

The Myth of Dry Feet

Abrams Creek at Hannah Mountain Trail

The Great Smoky Mountain National Park is a rain forrest. Average annual rainfall in the park ranges from 55 inches in the lower sections to more than 85 inches atop the ridges. To our great fortune, that water moves down the 2,900 miles of rivers and streams, over the spectacular falls and cascades that present the symphonies of water music and the lullabies that sing us to sleep. Some trails are known for their prolific number of stream crossings; Eagle Creek (17), Beard Cane (16), Lakeshore (15), Bone Valley (5 crossings in 1.8 miles) and others. Abrams Creek must be forded knee deep twice, at Hannah Mountain Trail and lately near the Trailhead on Rabbit Creek Trail with the bridge washed out. Rock hopping gets you over many of the crossings but ultimately, you will either slip or find there is not a suitable dry crossing. Rock hopping in winter is downright treacherous as invisible ice forms on rocks inviting your feet to land, only to land your bottom in the creek.

The Myth of the Waterproof Boot

Waterproof boots are better at holding water IN than they are keeping water OUT. And unless you never hike in the rain or always wear fisherman’s waiters, water will get into your boots.

Born To Run

Christopher McDougall’s book Born To Run was a deep dive in how humans were built for covering long distances on foot and how modern technology has actually interfered with our natural ability to do so. He lived with the Tarahumara Indians of Mexico to learn how they can run hundreds of miles day after day wearing no more than thin leather sandals. His hypothesis is that modern running shoe technology has provided too much cushioning and it impedes the natural movement of the foot and running gait leading to injuries. He cites research that despite high tech shoes costing north of $150 per pair, foot and leg injuries have gone up over the years. This has sparked a strange movement of barefoot runners and minimalist running shoes, which is a topic for another time. But the bottom line is that over-cushioned and stiff soles, interfere with the way our feet flex and adjust to the terrain in which we walk. Notionally, we are better off with fewer restrictions in binding our feet in shoes.

Christopher McDougall’s book Born To Run was a deep dive in how humans were built for covering long distances on foot and how modern technology has actually interfered with our natural ability to do so. He lived with the Tarahumara Indians of Mexico to learn how they can run hundreds of miles day after day wearing no more than thin leather sandals. His hypothesis is that modern running shoe technology has provided too much cushioning and it impedes the natural movement of the foot and running gait leading to injuries. He cites research that despite high tech shoes costing north of $150 per pair, foot and leg injuries have gone up over the years. This has sparked a strange movement of barefoot runners and minimalist running shoes, which is a topic for another time. But the bottom line is that over-cushioned and stiff soles, interfere with the way our feet flex and adjust to the terrain in which we walk. Notionally, we are better off with fewer restrictions in binding our feet in shoes.

A Pound On Your Feet Adds 5 Pounds To Your Back

This axiom has been around for decades. There’s a great article by Akweli Parker that cites research by the US Army stating “Weight on the feet is disproportionately more exhausting than weight carried on the torso.” The conclusion was that “carrying an amount of weight on the feet required between 4.7 and 6.4 times as much energy as carrying that same weight on one’s back.” So this venerated folktale wisdom seems to have to scientific backing.

Blistering Heat

The source of blisters is almost always bad fitting shoes, meaning shoes that are too small and too inflexible. Blisters are caused by friction. While excess movement can be a contributing factor, it’s the conditions of that movement that actually lead to the burns. Rigid inflexible shoe soles cause the feet to move inside the shoe. Built up moisture softens the skin and worsens the effect of excess movement. Feet also like to move in the shoe. Shoes that are too small restrict the natural movement of the feet (such as the toe region) and force the movement toward the pads of the feet. Feet swell when hiking. Tight fitting shoes displace this natural movement to other parts of the feet that are more prone to blisters.

The Water’s Fine…

It was perhaps in the Pretty Hollow Gap area, after several unsuccessful attempts at rock hopping that an epiphany struck. I have spent a lot of money and tried a lot of tricks (gaiters, wrapping my feet in plastic trash bags, no really) and hopped (slipped on) a lot of rocks and carried heavy sandals and expended a lot of stress and emotion… all in the quest of dry feet. On this day, it rained and when it rains, you give up to being wet. In that moment, I unconsciously quit worrying about getting my feet wet. It simply didn’t matter anymore. Then my mind played a strange trick on me. It brought this thought to my consciousness. When you’re not worried about getting your feet wet, rock hopping is no longer an imperative. Then you realize that wet feet, once they’re wet, are not so bad. It became one of those existential questions; “Why am I here?”, “Where did I come from?”, “Why am I afraid to get my feet wet?”. Water is the stuff of life. It’s one of those things that made life possible on this third rock from the Sun. I was freed that day of the fear of wet feet.

It was perhaps in the Pretty Hollow Gap area, after several unsuccessful attempts at rock hopping that an epiphany struck. I have spent a lot of money and tried a lot of tricks (gaiters, wrapping my feet in plastic trash bags, no really) and hopped (slipped on) a lot of rocks and carried heavy sandals and expended a lot of stress and emotion… all in the quest of dry feet. On this day, it rained and when it rains, you give up to being wet. In that moment, I unconsciously quit worrying about getting my feet wet. It simply didn’t matter anymore. Then my mind played a strange trick on me. It brought this thought to my consciousness. When you’re not worried about getting your feet wet, rock hopping is no longer an imperative. Then you realize that wet feet, once they’re wet, are not so bad. It became one of those existential questions; “Why am I here?”, “Where did I come from?”, “Why am I afraid to get my feet wet?”. Water is the stuff of life. It’s one of those things that made life possible on this third rock from the Sun. I was freed that day of the fear of wet feet.

And So…

When you embrace the inevitable fact that your feet will get wet when you hike 900 miles in the Smokies, it opens up new possibilities to how your dogs are shod. You no longer require waterproofness. In fact, you will seek a shoe that leaks like a sieve because you want the water to have an easy exit. It’s not about the presence of moisture but the amount and where it goes. This is a thing that will confuse the sales person at the outfitter as they try to convince you to buy expensive GoreTex; “No, please show me your lightest, most leaky shoe first.” Chota makes shoes for canoeists who paddle the Boundary Waters of Minnesota. The proper way to ingress a canoe is to walk into the water with the boat afloat and step into it. Wet feet are a given. Chota actually puts little vents on the insoles of their shoes so the water can flow right out. I have been known to punch a couple small holes in the insole of my hiking shoes. When I ford a creek, my feet are pretty dry within a half mile or so of hiking because the water works it’s way out of the shoe pretty quickly. Slightly damp, yes. Soaked no.

Sock It To Me

The old school traditional wisdom on socks was to wear thick wool socks with thin polypropylene or silk sock liners. This was in the era of heavy full grain leather mountaineering boots, which were about the only option available to hikers back in the day. The wool socks were padded and insulating and the liners were for wicking moisture away from the skin. Since the liners couldn’t absorb and keep moisture, the feet remained slightly damp rather than completely soaked. Plus, the liners served as a second skin to guard against friction. Some lightweight guru along the way asked a simple question. “If my shoes drain well, why do I need the thick socks?” Ray Jardine advocates cheap men’s dress socks which you can buy for 3/ $10 at your favorite discount retailer.

The Cold Truth

Snow on Maddron Bald Trail

It’s been my experience that hiking keeps your feet warm. Even in the winter through snow. Most 900 Milers avail themselves of the off-season, especially for the more popular trails. I hiked Maddron Bald the end of February in 8 inches of snow. If it’s winter and you hike above 4,500 ft., you’ll hit snow. Yes, my feet get wet and cool. But I never have a problem with severe cold. When my hiking is suspended for the day, I make sure to have dry warm socks and in the pack.

Soul of the Sole

My ideal shoe is the lightest, leakiest, reasonably flexible, least padded, cheapest shoes I can find. I pair them with thin ankle high merino wool socks. I have about 600 miles on a pair of Salomon XSCREAM trail runners. They weigh together 1 lb. 6 oz. They only have a few miles left and I will be sad to retire them. As far as I can tell, Salomon discontinued the model and replaced them with the X Mission 3. One of the gripes I have with gear providers is that in order to project cutting edge design and a sense of what’s new, they tend to retire good products for no other reason than they are so last year.

My ideal shoe is the lightest, leakiest, reasonably flexible, least padded, cheapest shoes I can find. I pair them with thin ankle high merino wool socks. I have about 600 miles on a pair of Salomon XSCREAM trail runners. They weigh together 1 lb. 6 oz. They only have a few miles left and I will be sad to retire them. As far as I can tell, Salomon discontinued the model and replaced them with the X Mission 3. One of the gripes I have with gear providers is that in order to project cutting edge design and a sense of what’s new, they tend to retire good products for no other reason than they are so last year.

My feet have never been happier since I went lightweight and free flowing. I rarely blister and I don’t have aches and soreness from moving against rigid hard soles. My preference is still to rock hop creeks if reasonable but a good soaking is no longer the end of my happiness.

Of course, I could be wrong…

Shalom. Strider out…

Shalom. Strider out…

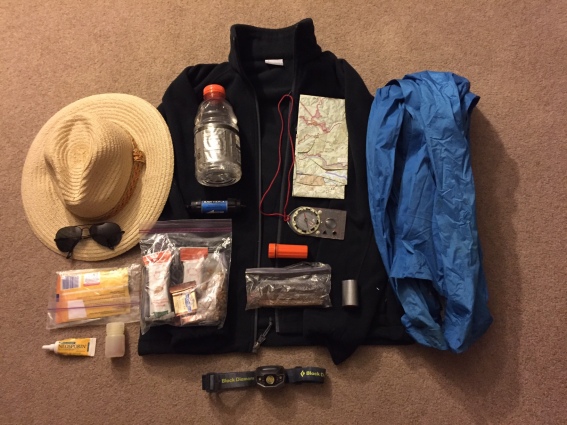

When it’s raining outside and you are too wimpy to go backpacking in it, you go through your gear, weighing everything in preparation for the obligatory gear checklist. And of course, the picture of your possessions in the House on Your Back. On the gear spectrum, I tend to fall near the ultralight folks but I am willing to make compromises for comfort and convenience and I readily admit this list is somewhat flexible. I own no Cuban fiber. But just for kicks, I did cut the handle off my tooth brush and I have been known to trim the borders off my maps.

When it’s raining outside and you are too wimpy to go backpacking in it, you go through your gear, weighing everything in preparation for the obligatory gear checklist. And of course, the picture of your possessions in the House on Your Back. On the gear spectrum, I tend to fall near the ultralight folks but I am willing to make compromises for comfort and convenience and I readily admit this list is somewhat flexible. I own no Cuban fiber. But just for kicks, I did cut the handle off my tooth brush and I have been known to trim the borders off my maps.

There are a number of things that make hiking out west different from hiking in the Smokies. Elevation is one thing. From what I can tell, I’ll be spending most of my time above 10,000 feet. Mt. LeConte is 6594′. Clingmans Dome is 6644′. The tallest mountain in the east, Mitchell, is 6683′.

There are a number of things that make hiking out west different from hiking in the Smokies. Elevation is one thing. From what I can tell, I’ll be spending most of my time above 10,000 feet. Mt. LeConte is 6594′. Clingmans Dome is 6644′. The tallest mountain in the east, Mitchell, is 6683′.

Shalom. Strider out…

Shalom. Strider out…